Imagining and Managing Trade of Labor Automating AI

AI companies expect their products to automate large swathes of jobs

Already, AI can augment some work tasks performed by many people, and it may soon automate most tasks performed by some jobs. Today, it looks like these AI workers will be agents. In January, OpenAI announced Operator, a ‘Computer-Using-Agent’ (CUA) that can conduct tasks which would have been too memory intensive to accomplish just a few years ago. Anthropic has coding agents too, and both companies are currently trying to understand the economic impacts of their products. Anthropic has analyzed over 1,000,000 conversations with Claude Sonnet 3.7 and estimates that today, about 40% of occupations listed on the Department of Labor’s O*Net use AI for about 20% of their tasks. Looking forward, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman imagines AI’s impact on labor to be increasingly transformative, writing “we expect that “this technology can cause a significant change in labor markets (good and bad) in the coming years.”

These companies would not run labor market impact assessments or hire a chief economist if they weren’t anticipating that their models will significantly change the economy. Third party evaluators expect that too, since models are increasingly capable of completing work tasks and they are measurably cheaper in their work than human labor. METR recently showed the length of tasks AI can complete are doubling every 7 months, and they have also found that AI agents can perform tasks for approximately 1/30th as much as a median BA holder. With Google apparently using AI to produce about 25% of code and companies like Klarna using AI to handle two thirds of customer chats, the future feels close. How much time remains before total automation takes hold is entirely unclear. Look no further than the continued viability of the fax machine in American businesses today.

Whatever the pace, labor automation is coming. Aside from “when,” all that remains to be seen is for whom and to what extent. There is consensus that AI automation will be transformative, but the full implications of that transformation are rarely considered in the context of international trade. This bears consideration because:

- Companies developing labor automating AI will want to sell it in foreign markets.

- Governments of AI-importing countries will need to balance the interests of their firms and workers with careful trade policies.

- Automating labor in a global economy will likely twist national strategy around comparative advantage and terms of trade for bot-importing and exporting countries of AI agents.

- Trade of this digital service confounds trade models.

- Korinek and Acemoglu show that automation increases the capital share while reducing the labor share, increasing GDP growth while decreasing wages in importing and exporting countries.

A collapsing labor share from domestic automation has different policy frictions than a collapsing labor share from imports. Even if the end result is still substitution of capital for labor, trade and immigration policy instruments like tariffs or fines might be used in an attempt to prevent unemployment from imported AI services. On the other hand, domestic policy might utilize different tax regimes for labor displacing AI developers. Tax schemes and redistributive government initiatives would look different in either case.

Korinek, Stiglitz, Acemoglu, Autor, and others have deeply explored possible automation scenarios within a given country. My sense is that much more consideration has gone toward imagining policy measures such as universal basic income to limit economic harms and worsening inequality, and much less thought has been dedicated to similar international interventions. For example, a Windfall Trust aspires to tackle this problem after an AI firm reaches 1% of global GDP. However, national economies might bear negative impacts before such a milestone is reached.

As Korinek and Stiglitz put it in 2021, “when technological progress deteriorates the terms of trade and thus undermines the comparative advantage of entire countries, then entire nations may be worse off except if the winners within one country compensate the losers in other countries…”

How labor automation might work as a service

AI agents that automate tasks or whole job categories will likely work more like a B2B SaaS version of ChatGPT, Claude, or R1 than many traditional digital platforms like social media, search, streaming, dating apps, and intermediating marketplaces. OpenAI, Anthropic, Deepseek, or whoever else would essentially be selling licenses to improved and specialized versions of their frontier LLM, wrapped in the layered agentic scaffolding necessary to perform the tasks they are ‘hired’ to do. Like Microsoft Office or Zoom, ChatGPT currently charges monthly fees for the license to use the “Plus” and “Pro” tiers of capability.

In the case of labor automating AI, they may stick to this model or consider charging a rate based on how much cloud computation (i.e. charging per token) an agent actually utilizes in the performance of its tasks (Manus currently charges a monthly fee with a token limit, for example). Firms would be the end user, who are charged a fee for the ‘employment’ of the agent, which could perform general or specialized tasks as well as (or better than) most humans.

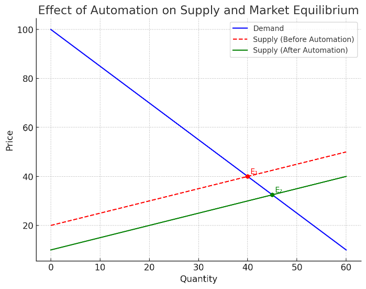

As long as AI can perform tasks comparably well to humans, companies will be compelled to utilize them on the basis of low cost relative to human employees. Firms that can increase production capacity at the same (or lower) marginal cost will be able to profit at lower prices than their competitors, who will be forced to adapt to compete. AI will probably be much better than people at some tasks, which will further incentivize its adoption. The graph above illustrates how automation might meet a greater labor market demand.

One Partial Solution: Not Digital Work Visas, but Digital Worker Visas

“Visas” for AI agents to mitigate social impacts of automation

Trading a labor automating AI means this product will work like a good economically, but will have political consequences similar to immigration. When the unmet demand for labor is met by international supply, that’s migration. In order to mitigate the social and economic negatives of that migration, one classic tool at a state’s disposal are visas. Visas offer an economic remediation to states that lose out on payroll and consumption taxes, while serving as a political mitigation to international and domestic issues that immigration can create.

A visa-like system could work because it allows importers to dictate the terms of trade, connecting economic needs with political means. Such a system might also standardize IDs for imported AI agents, enhancing AI safety and security via oversight capacity.

Migrant labor is accepted into host countries for a variety of reasons. Depending on the domestic labor supply in a given country, high-or-low-skilled labor might be in high demand. The U.S. has a demand for both that is met by high-skilled H1B migrants in AI labs and undocumented migrants in low-skilled agricultural and hospitality jobs, for example. When the job market tightens though, these inflows can generate political tension between unemployed and underemployed citizens and migrant workers.

Countries operating on net losses of labor migration flows have the opposite problem: skilled workers who can seek better opportunities abroad tend to emigrate. They take with them a tax base and weaken the demographic base of social security systems like pension, university, and healthcare schemes. The result is a negative feedback loop of fewer educated employees and businesses, lower national productivity, and spiralling fiscal deficits.

In wealthy countries, immigrants may even be accepted initially for some altruistic purpose such as to offer asylum, but this can be fraught with social and political issues as well. Permission to remain in-country is typically justified in economic terms such as:

- Migrant consumption of goods and services increase demand to compensate for displacement in the labor market.

- Migrants supply domestic labor demands that are not met due to insufficient wages or social prestige (e.g. agricultural labor in the U.S. or construction in the UAE).

- In the United States, migrant workers actually shore up social security by receiving taxes that withhold benefits from which they will never be legally able to draw.

For automation imports, visas could work as a tax to replace lost tax revenues or to fund new welfare programs. Admittedly, this feels hand-wavy. Excising a tax on importers in the form of a visa for AI agents might mitigate lost income from consumption-based taxes, but estimating (much less mitigating) the growth lost to automation in real estate, consumer goods, and other markets is unclear. Calibrating Pigouvian taxes such that profits of innovative technologies offset the cost of their negative externalities is extremely complex. Visa costs could help with this but would likely need to be one step in a broader strategy.

Visas as a tool of standardization, verification, and validation

A visa is a form of identification. It identifies the bearer as authorized to integrate with a national economy system while tying them to a country of origin. It empowers the government to track immigrants against quotas and may permit or prohibit the recipient to perform certain kinds of labor, such as those that require a security clearance or labor that could just as well be performed by a citizen (or domestic AI agent!). This could be one piece of a greater AI agent infrastructure.

Chan et al. show that AI agents might have IDs that demonstrate provenance to facilitate attribution of responsibility and liability, but also as a means of connecting a given agent to a model card, benchmarking specs, or other valuable safety information. Just as various ID is needed to transition from foreign national to permanent resident, some series of identifiers might facilitate a labor automating AI receiving a work visa. This would contribute toward mitigating issues by:

- Policing harmful practices of illegal activities or untaxed gray market AI labor, and potentially helping to analyze incidents;

- enhancing state capacity to track how many AIs are performing tasks in their country; and

- issuing revocable work permission for ‘AI labor automation trial runs.’

Visa costs can scale with impact

Visas to AI agents in the future might be issued for an up-front nominal fee, just as US firms today have to pay approximately $10,000 for H1B visas, and extending it could cost up to $18,000. Presently, this visa is for highly skilled professional talent, which would be the type of tasks that AI developers and economists expect AI to automate soon. Producing at a human level of volume for a much lower marginal cost, this may be a reasonable starting point.

Down the line, as AI tools expand in productive capability and as they begin to automate ever more tasks, the value created by AIs should become harder to quantify in human terms. Human workers are paid wages approximately in proportion to the value that they create, but AI agents producing multiple times the hourly output of a human might have to charge on the basis of tasks completed rather than hours or days worked. The relative value of human labor might plummet.

States might levy taxes on inference to capture the economic value of work tasks computed.

If the economic benefit of AGI or ASI agents is multiple orders of magnitude greater than human output, companies might have no problem agreeing to let the government visa tax system siphon off nominally huge but percentually moderate revenues to mitigate increasing automation.

Conclusion

AI developers develop increasingly capable systems in large part to automate economically valuable tasks, so policy makers and researchers must take labor displacement seriously. Commonly, mitigations like universal basic income are proposed. Other stakeholders might move to legally protect workers from losing their employment to automation. But UBI takes a one-country view of the problem, and banning automation might prevent AI from creating benefits to productivity and efficiency. These interventions are at best partial solutions to what will be a worldwide challenge, and they obfuscate the rational motives that firms and countries will have to adopt and promote labor automating AI.

Exporting countries may collect enormous rents from early leadership in automation such as by deepening platform lock-in, expanding trade surpluses, strengthening soft power, and solidifying political legitimacy. But the benefits will be unevenly distributed and will probably lower wages broadly, since marginal labor input in this model is negligible. Importing countries may enjoy a temporary boost in productivity and competitiveness, particularly in sectors constrained by skilled labor shortages or demographic decline, but will also face intensified distributional pressure, transformational effects in tax bases, and new regulatory challenges.

In trade terms, this technology does not conform to existing frameworks. Labor automating AI is a high-scale, low-marginal-cost service governed by platform dynamics and extremely mobile factors, not by traditional factor endowments. Governments must conceive and apply various mechanisms to identify, meter, and tax cross-border automated work. The merit of those mechanisms will be judged not just by how well they allow firms to import a digital service, but by how the benefits of that trade diffuse among society.

One option laid out here is an AI agent visa regime that treats high-capability AI agents as labor substitutes, allows states to set quotas or sectoral conditions, and creates an avenue of taxation incentivizing governments to permit the uptake of automation and allowing them to capture revenue for social protection. A lighter-weight sequence of mandatory registration of foreign AI agents, reporting on sectoral usage, and progressive fees tied to impact could achieve similar aims and may be easier to coordinate. Whatever the instrument, leaving this to existing trade and cloud-services rules would amount to ceding policy control to a handful of exporting platforms. The choice is not whether to intervene, but how early and by what combination of rules to do so.