Why Countries May Want To Import And Export Labor Automating AI

I have written previously about trade of labor automating AI, which I see is as both an inevitable step in AI diffusion in the world economy. Elsewhere, I have written about why I think AI labor as a trade good breaks trade models like H-O, and later on I will have more to say about how importers can mitigate negative impacts of this disruptive technology. For now, this piece will consider very basic potential motivations for countries to engage in trade of labor automation. In the interest of simplicity, the following framework hypothesizes that the United States and China will be exporters of labor automating AI with the European Union importing. Please take this thought experiment with the following grains of salt:

- I do not personally exclude the possibility that European firms could one day have competitve AI models to export, just as the U.S. and China may be future importers

- I presume the Global South will have strong motivations for and against importing AI labor, something I’m still thinking about and hope to explore more deeply later; and

- My framing of automation implicitly considers jobs and tasks that can be conducted remotely, but these thoughts on trade do not necessarily preclude other task automation (ie robotics).

Domestically, the automation of labor seemingly benefits only the companies licensing AI workers, and the firms that will increase profit by replacing human employees with digital ones. We needn’t wrack our brains in search of potential negative economic, social, and political consequences of such a transformation. In the U.S., for example, consumption might drop precipitously if consumers face falling wages and spiking unemployment across sectors due to automation. Wealth inequality might explode, and new political movements would arise to manage class conflict and the needed reordering of society under this new paradigm. Anxiety abounds! But would Americans have the same anxieties about such a product being exported to other markets? Would other markets be insane to import the digital service of labor automation?

There are plenty of reasons to buy and sell labor automating AI in the global market. Given the stereotypical view of the European Union as an innovation-stifling regulator, there might be myriad reasons for the EU to discourage or ban labor automating AI. However, there are reasons why the bloc might import such a service too. For example, European companies might be induced to augment their staff with AI by competitive pressures against rival firms that benefit from the use of labor automating AI, or by shortfalls in labor supply created by emigration or EU employer regulations. Framed as ‘adopt or die,’ the choice seems obvious.

If automating knowledge work is advantageous, then early adopters ought to become ‘product champions’ as they accrue increasing returns to production from invested capital. International trade of labor automating AI will likely result in some of the outcomes that are expected in domestic markets, such as accelerating concentration of value into fewer “superstar firms.”

Note: superstar firms in a nutshell

Autor et al discuss how industry sales will increasingly concentrate in a small number of firms; the fall in the labor share will be driven largely by reallocation rather than a fall in the unweighted mean labor share across all firms; and these patterns should be observed not only in U.S. firms, but also internationally. They attribute superstar firms’ success largely to platform and network effects.

End note

There may also be benefits for economic growth among exporting and importing countries alike, even though there are likely to be winners and losers in both countries. For different reasons, wages should fall in both exporting and importing countries.

Let me lay out the case for engaging in trade of this technology that brings such mixed blessings:

Exporting from the U.S. and China

Why might the U.S. want to export automated labor, and why might China want to do the same?

1. Augmenting the U.S. digital services surplus

The U.S. is a consumer economy, and a wealthy importing nation. Despite running trade deficits generally, America ran a surplus of nearly $300 billion in services last year. This is powered largely by American tech firms, whose size gives them a dominant position in open markets without a competitive tech industry. Although it isn’t necessarily good nor bad to run deficits in trade, there can be political value in a robust exports market.

2. Strengthening the U.S. dollar

Buying American goods and services increases the global demand for dollars, causing an appreciation relative to other currencies. Increasing demand for U.S. dollars, along with a strong demand for U.S. treasury bills, is key to America’s ‘exorbitant privilege.’ This privilege allows America to run less burdensome fiscal deficits than other countries could by dint of large global demand keeping the dollar value high and interest on U.S. debt low. I assume that dollar appreciation from the export of a very highly demanded digital service would cause similar effects to the Dutch Disease for U.S. consumers, as imports of foreign-denominated goods and services become relatively cheaper. As a consumption economy that buys many more goods than it sells abroad, this works for Americans.

Typically, the corollary of expanding exports would be rising wages, but in this case that is contradicted by a variety of factors. First, under neoclassical theory, we should see growing exports draw labor to produce more of the exported goods, the demand for which labor would increase wages and pull the marginal cost of production up. But this would not happen here because the marginal human labor required to make additional AI agents foreign countries demand ought to be near zero. Likewise, one might expect model training and AI R&D to be a large up front cost that is being paid off more so than a subsequent investment with tech firm revenues. So, the return from trade is almost all to capital.

The only cost that should go up from increased demand of these exports is cloud inference compute to serve growing volumes of AI agent activity, the physical servers for which may not even be onshore (from a US perspective), further limiting any possible effects in U.S. wages from trade. If American agents in foreign markets are making calls to data centers not located in the United States, then any new data center staff hired would most likely not be American anyway.

If there were any American wage growth, it should be isolated to the high-skill labor and capital like AI engineers, which would be beneficial only to a relatively small, specific, and already high-earning workers segment. This, of course, would assume that labor automating AI continues to be made by humans.

3. American superstar firms become more powerful

America’s largest firms by market cap are engines of capital generation and they invest huge sums into research and development. The returns to capital from this trade would benefit the best capital endowed, which should allow for the continued specialization of America into capital-intensive activities. As of this writing, the market caps of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and Nvidia sum to about $20 trillion USD. When considering them together, they constitute a significant driver of American economic growth that produces several U.S.-favorable spillovers.

In addition to growing GDP in the U.S., these firms help to extend connectivity to the world by exporting cloud computing to markets that might lack the initial capital to develop indigenous hyperscalers. By paving the world’s internet highways, these firms also standardize American products and practices globally, further entrenching themselves to perpetuate a cycle of enlargement and returns to scale. These firms are the obvious candidates for first movers and early winners in AI exports, and the default U.S. economic strategy is probably to allow them to continue innovating, diffusing, and achieving transformative AI.

4. Better world productivity improves world trade

If firms are able to increase marginal productivity through improved processes or cheaper additional labor inputs as a benefit of utilizing labor automating AIimported by American or Chinese AI model labs, they should enjoy economic benefits from trade of all goods and services whose production value is improved by labor automating AI. An influx of automation should be useful in industries from European manufacturers to India software engineers and any number of firms and SMEs in Africa. An example of this in action might be cheaper European cars and faster Indian software engineering for Americans to buy with their stronger U.S. dollars. Utilization of labor automating AI exported by the U.S. would enable returns to scale for AI producers with high large fixed costs and small marginal costs, generating benefits to U.S. exports.

China exporting

1. Diversifies Chinese export goods

Chinese exports that depend on low labor costs have been instrumental in industrializing the country and combating poverty there. Cheap labor has not been China’s competitive edge for some time, however. China wins on cost now because of efficiency, automation, cheap energy, and other benefits of scale. For cheap labor, western firms are now more inclined to put factories elsewhere in the region, such as Vietnam or Malaysia. Still, it’s important that additional exports be added into the mix, to hedge against economic harm from a sudden loss in exported physical goods.

Chinese firms like Huawei, Bydu, TCL, SMIC, and others are already competitive with other high tech manufacturers in the world, but they have to expand foreign sales to offset major government subsidies. Expanding into digital services is a key part of the Made in China 2025 Initiative to revamp manufacturing and high tech industries, and expanding the Chinese basket of goods for export can help hit those ambitious targets while hedging against potential declines in competitiveness on the basis of low labor costs.

2. Exporting labor automating AI as a new mercantilist strategy

As stated in the U.S. case, expanding exports puts upward pressure on domestic currency value. Even if the yuan appreciates, a high net export of digital labor could allow China to maintain trade surpluses. Chinese strategy has long been to keep their currency relatively weak so as to maintain price competitiveness on exports. This keeps their trade account positive but makes them averse to appreciation. Exporting labor automating AI could risk upsetting this strategy if it becomes a highly successful export, but it also might represent a good that Chinese firms can export regardless of currency appreciation. If enough foreign markets could become dependent on China for relatively cheap imported AI labor, rather than depending on China for relatively cheap imported goods as has traditionally been the case, then China may be able to liberate itself from a dependence upon manufacturing and currency valuation strategies for national growth.

3. Building up Chinese soft power

American soft power comes from a variety of sources, such as development financing (RIP USAID), influential culture (blue jeans, rock, rap, film, etc.), and also digital services (Netflix, social media, and cell apps). Cultivating international influence is strategically valuable to China, who has invested heavily in international development and multilateral governance fora as well. From a position of relative power and advantage in frontier AI model capability, China could utilize professional AI labor to send thousands of cheap teachers, tech workers, lawyers, accountants, and marketing specialists to any developing country with an internet connection. Countries that lack robust connectivity could also simply come to China for data center construction with Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) funding.

In 2024, BRI topped US $70 billion in construction projects, $51 billion in funding, and over $30 billion in total Chinese engagement in the technology sector (predominately supporting electric vehicles, PV solar panels, and batteries). The Chinese initiative for international development BRI has had mixed reactions. It has helped many countries to build local infrastructure via financing and construction contracts to Chinese builders, while being accused of predatory loans or not doing enough to teach locals to maintain their new roads and dams. Though these critiques have been broadly disputed and largely dismissed, Chinese exports of digital professional services would both contribute to development activities along a new dimension and cast the world’s leading manufacturer in a new light. Improving China’s reputation internationally can have real economic benefits. It increases preference for Chinese trade goods as a brand and can attract tourism, for example.

4. Political stability

I think it’s fair to generalize across most countries, not just China, that political legitimacy and continuity derives from economic stability. But, I think this is more true in East Asia than in the West, and uniquely so in China, where economic growth might substitute for democratic institutions in political legitimacy. The so-called “East Asian Miracle” offers a thorough explanation for the rise from poverty of 8 high performing economies from 1965-1990, and the short version is that a winning strategy for East Asian economic development incorporated many elements such as gender parity, openness to new technology, national education, and agricultural to industrial economic transformation. Part of what makes East Asia and China fundamentally different from the USA has been a smaller internal market and therefore dependence upon exports for growth throughout the past century or so.

This dependence on exports makes them subject to global markets and currency volatility, and that means exposure and vulnerability to shocks that is a lesser part of more developed western economies. Controls on credit, currency price controls, and dependence on foreign capital were ways of optimizing export growth in some East Asian countries but it also opened the door to financial crises spreading rapidly from foreign markets. Cutting this digression short, accelerated growth from an exported AI labor service could drive growth that supports China’s economic growth, export diversification, fiscal and monetary stability, and therefore political stability.

Importing labor automating AI to the EU

1. Increasing TFP shifts the PPF outward

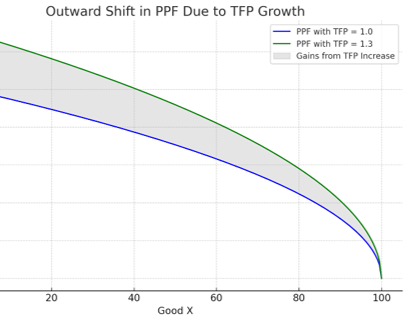

This is probably the main motivation for any country to import labor automating AI: it increases total factor productivity. Krugman talks about this in The Myth of Asia’s Miracle. In short, countries want to increase economic growth, but doing so only by increasing the inputs you throw into growing your economy is not really development. Instead, what they really want is to increase total factor productivity (TFP). TFP growth means that a country can produce more goods without increasing inputs of capital or labor. Although generally understood as ‘the portion of output growth not explained by increases in inputs,’ TFP growth is usually attributed to technology. It should be the most important variable but it is exogenous. The graph illustrates increased output of either good at the same input level of each.

2. Cheap skilled labor

AI automation offers “labor on demand” in sectors where the EU has an insufficient supply. As stated in a report titled The Future of European Competitiveness, from September of 2024, projections to 2035 indicate that labor shortages will be worst in highest-skilled, non manual fields, which is where AI seems best positioned to complete tasks. The report attributes these shortfalls to brain drain (Europe’s best engineers often seek higher salaries abroad), slow adoption and creation of innovative technology, and declining birth rates. Where a shallow talent pool is the bottleneck to growth for European companies, automation could be a fix by working like labor on tap.

European auto manufacturers like Volkswagen utilize AI technologies to improve processes of design, research, and manufacturing, and the car industry is a classic use case for automation through robotics. Importing automated labor to revolutionize other sectors could be another step in the same direction of productivity-enhancing technology adoption. Cheaper production of more, better vehicles per year will be a difficult opportunity for firms. Countries like Germany and Italy that historically are highly dependent on manufactured exports would theoretically see cheaper skilled labor as an opportunity.

3. Addressing population decline

SMEs and startups could leverage specialized AI agents to prototype, market, and scale faster, without large fixed labor investments and social frictions over immigration reform. Over decades, population decline might cause shortfalls in labor across some sectors, and automating those sectors could be a solution. At the national level, importing digital labor could help to decouple GDP growth from labor force size.

4. Preserving welfare models

If GDP in EU countries grows faster with imported AI labor than without it, it would be worth the trouble to take on a more negative trade balance. Generating more national income can support countries like Italy, whose high GDP to debt ratio threatens a social welfare crisis in the eventuality that it struggles to meet the healthcare and social insurance obligations to its citizens. Employing AI can increase national productivity while also reducing the number of beneficiaries of national health insurance and pension schemes. By substituting AI labor, firms can stay competitive without gutting labor protections, allowing European welfare states to potentially survive globalization pressures better than if human offshoring were the only alternative.

5. European Union can focus on regulation

If EU fragmentation makes it impossible to capitalize large AI foundation model development, it might benefit from trade by just importing those services from the U.S. and China. Europeans have anxieties about AI and most want it regulated. Regulation and bureaucracy creates the “Brussels Effect” which compels foreign digital services to respect European laws and values. This limits its ability to develop European AI models but has positive effects on global adoption of technology by requiring interoperability (e.g. iPhones now use USB C for charging instead of proprietary lightning cables) and rights respecting data governance (“the right to be forgotten” seems like a good thing). As strange as it may be to frame EU red tape as a good thing, the EU’s large consumer market of 500 million people gives it the leverage to confront anticompetitive practices by the likes of AWS and personal data record keeping by Google and Meta, for example.

Persistent ambiguity for all parties

For all countries, automating labor ushers in profound uncertainty. The scenarios outlined above help to show the incentives for proceeding with trading labor automating AI, and those motivations are sometimes contradictory. The U.S. expanding its exports could hurt domestic job growth. Chinese exports of digital services could cause self-inflicted harm via currency appreciation. Importing automation services could exacerbate the very unemployment problems that lead to emigration. Making capital and labor near-perfect substitutes is bound to create some paradoxes, after all!

Yet states pursuing AI strategies that end in advanced AI and AGI should be rationally fearful of success. Winning in this case has the consequence of empowering a few firms and transforming the structure of the 21st century economy and international trade along with it. If labor is to cede ground to automation, then a balance must be struck between the future relationship between prices and wages. Governments need to plan so that they do not become victims of their own success. The difference between technological advancement facilitating utopian or a dystopian futures is down to the choices of voters and policy makers.